Your Guide to the Drone Age

Drones have been around for decades. Governments are frequent fliers, along with some industries. Consumer drones have become a game-changing device for a niche-but-passionate group of hobbyists, creators, and entrepreneurs.

But the most starry-eyed predictions about commercial drones remain just that. For 99% of the world, autonomous drone delivery is not right around the corner. We’d bet that most of you reading this don’t see drones in your day-to-day lives. And don’t even get us started on flying cars.

Before we digress into full-on Jetsons comparisons, let’s get definitions out of the way. A drone can simply be described as a flying robot. It’s an aircraft sans onboard pilot, typically controlled by someone on the ground. Drones are often envisioned as automated machines that fly without human input or guidance.

- Related vocab terms: unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) or remotely piloted aircraft systems (RPAS). We’re going to stick with the word “drone.” It rolls off the tongue.

I. Booting up: A Brief History

II. Flying Smartphones: The tech powering today’s drones

In terms of shape and size, drones almost rival the animal kingdom in their breadth of diversity. Let’s illustrate that:

- DJI’s Mini 2 retails for $449, weighs less than a full water bottle, can stay in the air for almost half an hour, and can fly a few miles away.

- Northrop Grumman’s RQ-4 Global Hawk costs more than $123 million, has a 131-foot wingspan and 48-foot length, and can survey up to 40,000 square miles (Iceland) in a day. The Hawk has stayed in the air continuously for over 33 hours.

While we’re here: Military drone usage and the accompanying ethical considerations are hugely important topics, but they’re beyond the scope of this guide. The following sections unpack drone technology in commercial and consumer contexts.

Today’s drones are the direct beneficiaries of yesterday’s smartphone revolution. The shift to mobile computing created economies of scale for miniaturized parts: processors, sensors, batteries, and wireless relays. And everything gets better, smaller, and cheaper by the year.

- These profound shifts mean that drones can now take HD videos, track location, and send data to and fro, for just a few hundred dollars. A decade ago, that combination of technology would have cost an order of magnitude more.

- The $799 DJI Mavic Air 2 can shoot 4K video and intelligently avoid obstacles or track objects. The total cost of its components? A measly $135, per a Nikkei teardown.

Now, on to our own teardown:

Francis Scialabba/Ryan Duffy

Francis Scialabba/Ryan Duffy1) Rotors: Rotors are the spinning blades that push air up or down. Rotors are attached to motors.

2) Motors: A motor spins the rotor and enables movement. When a drone ascends, its rotors produce an upward force larger than its gravitational pull. The opposite applies during descent, as John Mayer quietly hums “Gravity” to the drone. Drones use motors to hover, so that thrust = gravitational pull.

3) Landing gear: How else is your drone gonna return? The more expensive a machine is, the more likely its landing gear is retractable.

4) Data link systems: Drones use frequencies to transmit and receive data. These communication modules provide a link between the air systems and ground control.

5) Battery: Batteries make up a sizable portion of a drone’s weight. The most common battery technology is lithium-based. Advances in energy storage technology will unlock longer flight times and new capabilities.

6) “Ground station”: Think of this as a remote controller. Consumer drones are frequently controlled with a smartphone or tablet, where a pilot can see a real-time video, GPS coordinates, battery levels, and other flight information.

But your standard drone packs way more components than what we’ve included in the above mockup. A quick rundown:

- GPS modules: These help a drone know its location by connecting to a web of satellites. GPS modules also enable drones to hold their position, auto-navigate by waypoint, or return home if communication with the controller is lost.

- Gyroscope: Measures rates of rotation and helps a drone determine orientation.

- Magnetometer: Measures Earth’s magnetic field to determine orientation.

- Pressure sensor: Measures atmospheric pressure to determine altitude.

- Accelerometer: Measures (shocker) acceleration.

- Compass: Drones have compasses, so they do not have to navigate by watching landmarks or stars.

- Gimbal: A pivoting support that rotates on the x, y, and z axes to provide stabilization for a camera or other sensor

- Collision avoidance sensors: Paired with machine learning software, this hardware helps your drone avoid flying into a tree.

Some other important terms before we move on:

Quadcopter

Quadcopter Payload

Payload Autonomy

Autonomy

Quadcopter

A drone with four rotors, and the model for our lovely diagram. In quadcopters, two rotors rotate clockwise, and the other two rotate counterclockwise. Software and computerized systems are working in tandem to process controller inputs so the drone’s components produce the pilot’s intended action.

- For instance, when you turn a drone, the software is slowing down one set of diagonal rotors and speeding up the other.

Technical barriers still exist, and they’ve held back drones from wider commercial deployment. Flight range is constrained by today’s power sources. Models that can go the distance and reach higher speeds have limited payload capabilities. Meanwhile, aircraft performance can be significantly degraded by weather and altitude. Radio frequencies from other sources can also interfere drone operations in urban centers.

III. Putting drones to work

Before we dive into relevant drone industries, we’d be remiss not to run through the top manufacturers. The dominant public-facing flying robot maker is DJI, which captures between 70% and 80% of the US consumer and enterprise drone market. Boeing and Airbus also make drones, as do a host of military contractors. Now, on to those industries:

- Military

- Energy

- Entertainment

- Real estate

- Agriculture

- Construction

- Delivery

- Emergency response

- Counter-drone

- Drone software and services

IV. Air Traffic Control

The FAA and its counterparts around the world are pivotal players in the world of drones. Compared with other emerging technologies where research and development may be running laps around law and regulation, drone policy is decidedly less laissez faire. Governments have chosen not to allow self-regulation, due to the high stakes of mission failure.

Rules for you: Rather than saying what you can do with your drone in the US, it may be easier to look at what you can’t do. You can’t fly at night. You can’t fly over 400 feet in altitude at night; beyond the visual line of sight; over people or cars; or from a moving vehicle. Don’t fly within five miles of an airport. And one person can’t fly more than one drone.

- If you want to fly a drone commercially, you must obtain a Remote Pilot Certificate. You must follow the above rules, unless you request and receive waivers and/or airspace authorizations from the FAA.

- If you’re flying recreationally in the US, you must register your drone with the FAA if it weighs 250 grams or more.

In December 2020, the FAA issued the Remote ID rule, which it called “a major step toward the full integration of drones into the national airspace system.” Remote ID is like a real-time digital license plate system, one that will require pilots to broadcast where they and their drones are.

- When Remote ID goes into full effect in 2023, it will (controversially) make many drones and hobbyist models illegal to fly unless they are retrofitted with expensive equipment.

- Popular off-the-shelf drones will likely just become more expensive. But this system could leave few options for a thriving open-source hobbyist community, which prefers to constantly tinker and build new models themselves.

Many other government agencies in Washington are also involved in drone affairs. The Department of Transportation, the FAA’s parent agency, oversees and regulates air carriage. The FCC allocates spectrum and frees airwaves for drone applications. NASA designs air traffic control systems. DHS watches out for security threats posed by drones. The FTC is the enforcer for matters of drone privacy.

- And as we found out in December, the Commerce Department can be involved, too: It placed DJI on the Entity List, which could cut off the dronemaker’s access to US parts and technology.

For scaled up commercial operations, public-private partnerships are the name of the game. States like North Carolina and Virginia have worked extensively with drone operators to get healthcare delivery pilots off the ground.

Companies with key drone certifications or waivers work closely with regulators. In an interview last year, a UPS exec told usthe company’s relationship with the FAA was a “huge asset moving forward,” as it received air carrier certification and worked toward wider deployments.

Beyond rules and regulations

In order for more drones to take flight, there are additional issues to consider beyond the law.

Local communities: In 2017, Pew asked Americans how they’d react if they saw a drone close to where they live. The data is slightly stale, but it’s the best we’ve got:

- 58% of respondents said they’d be curious

- 45% said interested

- 26%, nervous

- 18%, indifferent

- 15%, excited

- 12%, angry

- 11%, scared

With drone delivery pilots underway in towns and suburbs around the world, we have an early sense of what’s working and what isn’t. In Canberra, the capital of Australia, Wing is piloting drone deliveries of food. In 2019, the drones were found to be exceeding noise limits. The noise sparked a backlash from citizens, and, in response, Wing pledged to make its drones quieter.

Public safety: Reports of drone sightings in unauthorized areas continue to grow. In the last few years, we’ve seen a spate of high-profile incidents in which drones were spotted near airports and planes. At best, these incidents show reckless behavior and undermine the public’s trust in drones. At worst, they could lead to serious injuries or even a fatal accident.

Privacy: Drones can easily be used as surveillance devices. Police departments across the world are increasing their usage of drones. Amazon patented a “surveillance as a service” drone system. As drones become more common, expect more conversations about privacy.

In the 2017 Pew survey, 54% of Americans said they believed drones should not be allowed to fly near peoples’ homes. Only 11% think it should be allowed. We’d be very interested to see responses to the same topic now, with different types of pilots broken out. Are Americans any more comfortable now with a drone near their house? Does the answer depend on who’s flying it—private citizen, a company, or law enforcement?

V. Cleared for takeoff?

8% of Americans said they owned a drone in 2017, according to Pew. About 59% said they’d seen one in action. From March to November 2020, consumer drone sales grew 114% year over year, according to NPD’s Retail Tracking Service. We don’t have fresher population-level polling, but it’s safe to say both of those numbers have increased.

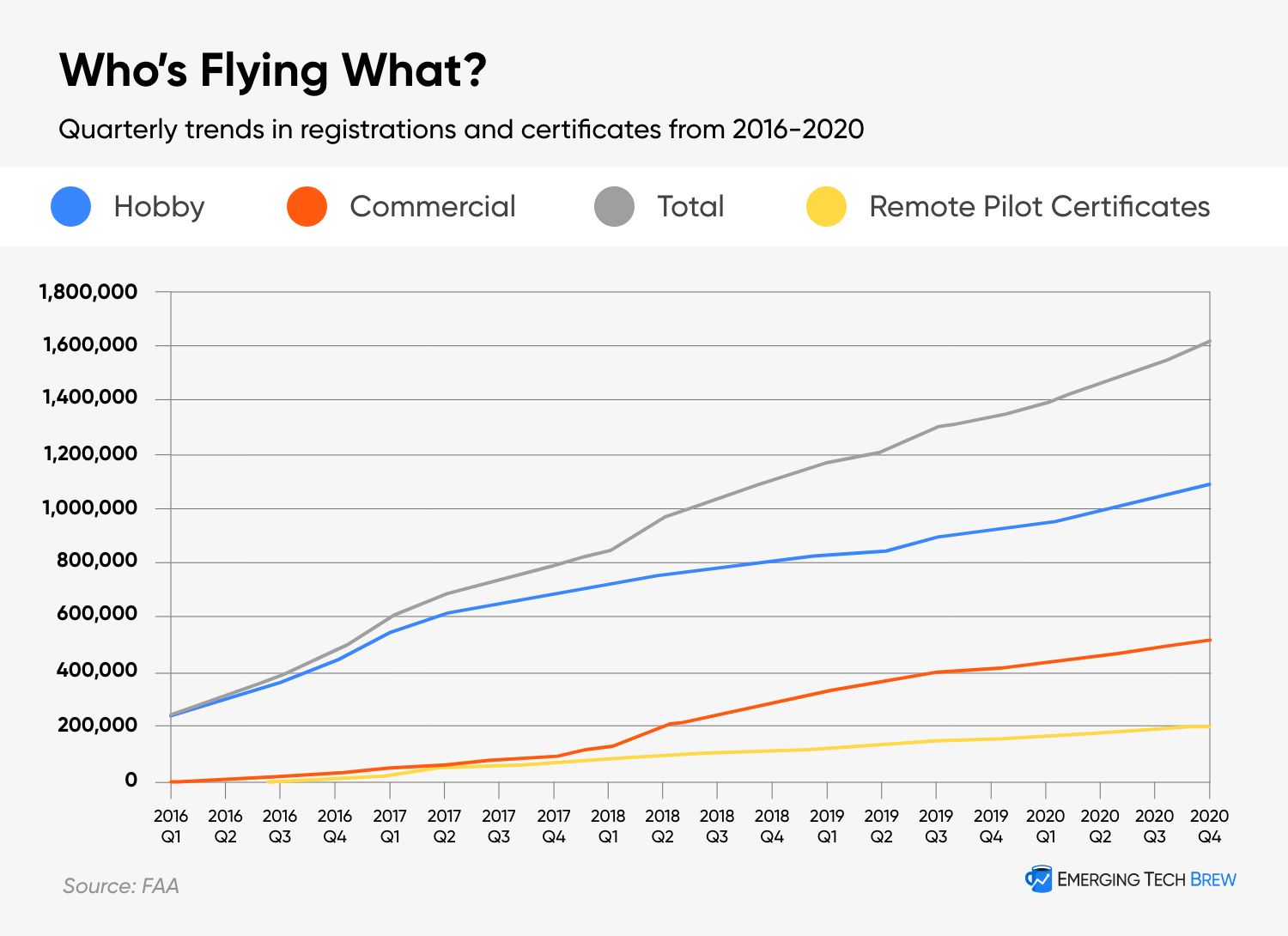

In terms of data we do have, here’s where we stand as of January 12 (h/t Uncle Sam):

- 1,746,248 total drones registered with the US government

- 510,758 commercial drones registered

- 1,231,990 recreational drones registered

- 203,036 remote pilots certified (including this writer)

Francis Scialabba/FAA/Ryan Duffy

Francis Scialabba/FAA/Ryan DuffyThose figures certainly blow one prediction out of the water: In 2012, the FAA said it anticipated “30,000 drones operating by 2020.”

The jury’s still out on the starry-eyed commercial delivery predictions. But from a workforce POV, drones are creating new roles and making other jobs more efficient, safe, and cost-effective. Two easy examples:

- A budget-conscious movie set gets plenty of options with a tricked-out drone and doesn’t need to rent a helicopter.

- In heavy industry, operators can use drones to access spots that would be unreachable or too dangerous for humans.

Drones’ clear benefits must be balanced against the drawbacks. There are privacy and noise pollution concerns. It goes without saying, but we’ll still say it: Safety and risk assessment are crucial. If a certain model has a 1/100,000th chance of falling from the sky, that may not work for an urban delivery service with a fleet of 20,000 autonomous drones running ten trips each per day.

But we’re not the only ones thinking about that. Safety is a paramount concern for drone developers and their regulators.

Source: MorningBrew